June 1, 2011 | Artists, Boris Mikhailov

A Conversation with Boris Mikhailov

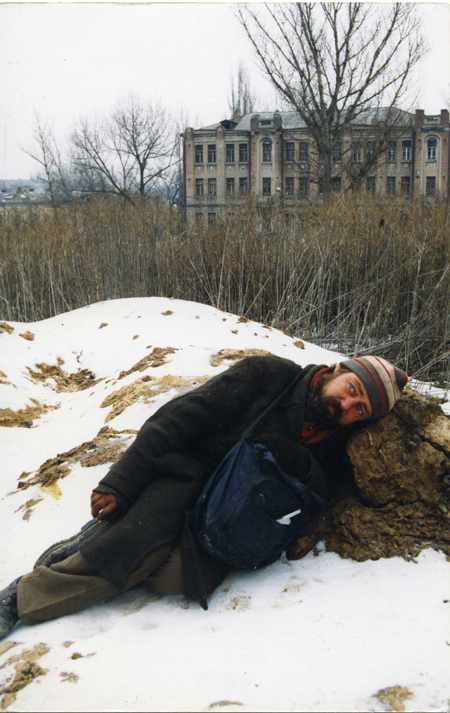

Boris Mikhailov. Untitled, from the series Case History. 1997–98. Chromogenic color print. Courtesy the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. © 2011 Boris Mikhailov

Once you see the pictures from Case History, they are impossible to forget. They are touching, devastating, and shocking. I feel that a museum should be a place that encourages debate and discussions presenting challenging ideas about the world. Boris’s work evokes many strong emotions and questions, so I asked him to share his thoughts about Case History.

Eva Respini: How did the series Case History come about?

Boris Mikhailov: What is truth or not truth? My feelings about this series have changed over time, so this is how I understand it now. I am from the Ukraine, but had been living in Berlin for a year on a stipend. After being away, I came back to my home town of Kharkov and it was very different from when I left. What was different? There were lots of color advertisements and other signs of the new capitalism, but when you looked more closely you could see a new society of people—the homeless.

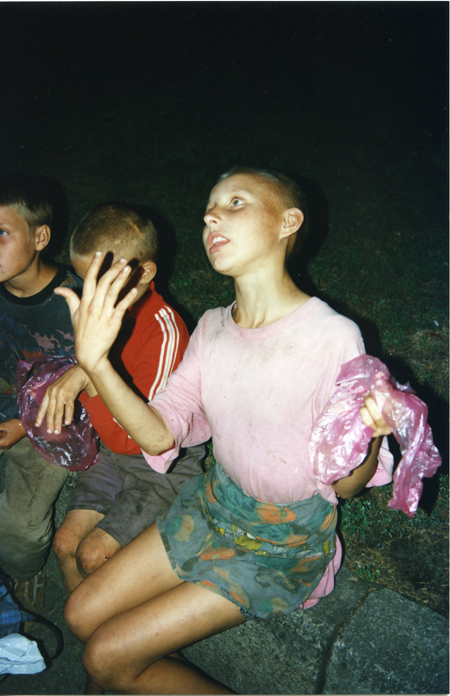

Boris Mikhailov. Untitled, from the series Case History. 1997–98. Chromogenic color print. Courtesy the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. © 2011 Boris Mikhailov

BM: There may have been some, but it was not common. Everybody had to have a job and the homeless were certainly not photographed. At that time it was illegal to photograph anything that made life and society look bad. For example, I was once arrested in Soviet times because I made pictures of people drinking, which did not fit into the Soviet propaganda. Now I was able to take pictures of what had been forbidden before, and this presented new possibilities to me as a photographer. With Case History, I saw it as my social responsibility to photograph these people. I saw how homeless people were helped in the West, but the government in the Ukraine had no money to do this. I think of the United States, when photographers like Dorothea Lange were hired by the government to photograph the Great Depression.

ER: How did you find the people in your photographs?

BM: First I should say that everything I do is in collaboration with my wife, Vita. When I saw somebody that I wanted to photograph, who was interesting to me, she would talk to them and help them. Then we would talk with them and collaborate with them to make a picture. They had no money, so I would pay them, to help them.

Boris Mikhailov. Untitled, from the series Case History. 1997–98. Chromogenic color print. Courtesy the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. © 2011 Boris Mikhailov

BM: This is the first time I paid my models. I don’t think this is an issue. If models get paid to appear in an advertisement, nobody cares. Why can’t I? This gave me the possibility to photograph them, and gave them the possibility to live. This is what Western photographers would do when they came to Russia to make pictures. The models would be paid as if they were posing nude at the art academy.

ER: I am glad you brought this up—there is a lot of nudity in the pictures.

BM: Nakedness is not important in many ways. Survival was important. You have to understand what was happening at that time. The Ukraine was very very poor, and everything was changing. Middle class people became poor and only very few people became rich. Ideas of modesty and morality were changing. Morality was broken, and prostitution was everywhere. I was trying to find a way to photograph this. These people posed nude without shame. Also, I had just come from Berlin, where there were plenty of nude people on the beach—there was a different idea of nakedness in the West.

Boris Mikhailov. Untitled, from the series Case History. 1997–98. Chromogenic color print. Courtesy the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. © 2011 Boris Mikhailov

BM: Documentary cannot be truth. Documentary pictures are one-sided, only one part of the conversation. Anyway, documentary pictures are not possible anymore with digital technology as nobody believes in the truth of pictures. These are real people in Case History. The only thing that changes is how they are posed and that they are naked. I posed these people in poses that remind me of the history of art or of gestures that I saw in life. Sometimes I asked them to repeat a gesture that they made so I could photograph it. With Case History, I wanted to find a metaphoric image of life. For example, how do you show prostitution? Nakedness doesn’t begin to describe this condition, so I asked my models to pull up their clothes as a metaphor for their life. For Case History, old documentary methods weren’t possible—it was important and necessary for me to find new methods to show this life.

Note: This conversation took place with Boris and Vita Mikhailov over lunch on May 20, 2011, and was transcribed and edited for clarity. Some responses were translated from Russian with the help of Vita Mikhailov.

No comments:

Post a Comment