http://chronicle.com/article/Whats-Wrong-With-Public/189921/

By Mark Greif

For years, the undigitized gem of American journals had been

Partisan Review. Last year its guardians finally brought it

online. Some of its mystery has been preserved, insofar as its format remains hard to use, awkward, and hopeless for searches. Even in its new digital form it retains a slightly superior pose.

The great importance of Partisan Review did not arise recently from its inaccessibility. The legendary items that first ran in its pages can be found in any good library, in collections by contributors who met as promising unknowns: Mary McCarthy, Clement Greenberg, Hannah Arendt, Saul Bellow, Elizabeth Hardwick, Leslie Fiedler, or Susan Sontag. Alongside those novices, PR had the cream of Europe, in translation or English original: Sartre, Camus, Jean Genet, Beauvoir; Ernst Jünger, Karl Jaspers, Gottfried Benn; plus T.S. Eliot, Orwell, Auden, Stephen Spender.

Partisan Review obtained the first work of the up-and-coming and often the best work of the famous, though it was notoriously underfunded and skeletally staffed. It gave readers the first glimpse of much of what would form the subsequent syllabus of midcentury American literature.

But Partisan Review has indeed mattered in more recent decades for its position in a debate to which its absence from view has been altogether relevant. More than any other publication of the mid-20th century, the journal has been a venerable stalking horse recruited into a minor culture war. The strife concerned what’s awkwardly called "public intellect"—that is, the sphere in which "public intellectuals" used to thrive. "Public intellectuals," as Russell Jacoby defined them near the start of this culture war, in 1987, are simply "writers and thinkers who address a general and educated audience." The customary sally was that PR exemplified a bygone world of politically strenuous, culturally sophisticated, and intellectually exacting argument standing in opposition to the university, because it was addressed to a broad, unacademic readership. It was said to be both more usefully influential and more rigorous than any forum we have now, reflecting poorly upon today’s publications and editors.Partisan Review stood as the phantom flagship of "what we have lost" since the late 1960s (the period in which the magazine began, not incidentally, its long-lasting decline).

Something has gone wrong in our collective idea of the "public."

A dozen years ago, as a graduate student, I sat down and started to read through the run ofPartisan Review on paper in the Yale library’s periodicals room. I completed the issues from 1934, the year of its founding, to 1955, when it started to lose energy. It was a thing of wonder, retaining a taut momentum for a score of years—powerful enough to engulf, for a month or two, a twenty-something who was otherwise agitated by the imminent Iraq invasion and eager to interrupt his studies to Google news from CNN, The Nation, The New Republic.

I read to two purposes besides curiosity. Foremost was the academic. I had begun research that would later ground a book it took me 10 years to get into shape—an alternative intellectual and literary history of the mid-20th century. The other purpose, 12 years ago, was starting the small magazine n+1. I had been something of a sucker for those calls for revived public intellectualism. Yet I knew how unsatisfactory their resolution had become. My co-founders and I—all of us planning together this unfunded magazine—imagined a joke headline to express where things were heading: "Solution to Intellectual Crisis: Senior Scholars Write Op-Eds." Maybe a younger generation could intervene? Both my library research and our creation of n+1 hid efforts to test the times. What about intellectual life after the turn of the 21st century? Wasn’t ours still the same world, rich with possibilities? What had we lost?

The discovery that most stayed with me from that naïve first reading ofPartisan Review was that, yes, it was impossibly good. It was better than I expected or could have imagined, maybe the best American journal of the century, or ever. There are yearlong streaks one could enter in which every article in every issue is compelling, from Winter to Fall (when it was quarterly) or January/February to November/December (when it was bimonthly), and at least one or two items in each number would be masterworks.

And yet: The precise ways in which it was excellent seemed very different from what was commonly said about it, or what nostalgists supposed. It especially differed from the supposed appeal to public-mindedness or a "general reader" as people understand it today. This has complicated much more for me the sense of "what we have lost"—to a degree that still confuses me. And whether we have lost anything that mere will, or "outreach" or "engagement," could ever get back.

If you ask the conditions that allowed Partisan Review to reach greatness—broaching an inquiry into what is necessary for the creation of "public intellect" in general, in the mid-20th century past—you face some unruly historical particulars.

First was the stimulus of the Communist Party USA. The magazine began as a youth-club publication of the party’s New York bureau. From 1934 to 1937, the editors championed Soviet dictates for proletarian writing, and the house tone bore the weight of party cant. A 21-year-old contributor went on maternity leave, and the editors praised her effort "to produce a future citizen of Soviet America." Then, from 1937, a change in cultural policy led the party to roll up its youth clubs, and two editors, Philip Rahv and William Phillips, took Partisan Review independent.

Second was the equalizing power of the Great Depression. With global capitalist collapse came expectation of socialist reconstruction and, more practically, a lot of free time, when so many, young and old, were underemployed and fractious. As William Phillips wrote in an early issue: "Most of us come from petty-bourgeois homes; some, of course, from proletarian ones. But the gravity of the economic crisis has leveled most of us (and our families) to meager, near-starvation existence." The editors held open houses to workshop fiction and poetry on weekday afternoons. Political independence for Partisan Review in 1937 still meant revolutionary socialism, just without Stalin. Freed from the party, though, its first-generation Jewish founders linked up with young American intellectuals, like Dwight Macdonald and Mary McCarthy, educated at Yale or Vassar, who brought in money and connections to keep the magazine afloat. The golden age of radicalism in politics, high modernism in aesthetics, and arrogance above all, which intellectual historians have most admired in PR, was launched by this combined demographic.

Then, World War II. This eruption pitched intellectual Europe into the New Yorkers’ laps. Internationalism had been a fixed principle already. But one expected the most important changes to occur on the Continent and its greatest minds to stay put there. By the early 1940s, the bulk of established European Jewish, leftist, or simply antifascist scholars and artists were on American shores, as refugees in the orbit of New York or Hollywood. Most were eager to meet any American group that would commit to them the same high opinion and intellectual interest they felt for themselves—and the "New York Intellectuals" were Europhiles. Though the editors of Partisan Review split internally in 1940 over U.S. entry into the war (with the renegades going to two new journals, politicsand Commentary), access to the ruin of Europe made them uniquely strong. It justified the juxtaposition of big names, internationally, with unknown Jews from the Bronx.

It also made the magazine institutionally potent. The combination of knowledgeable, left-wing anti-Communism with firsthand possession of a European émigré inheritance, all hammered together through American literary and artistic networks in the great metropolis, was a rare alloy. And as the United States emerged as the lone Western superpower, and its State Department sought to woo a rebuilt Europe away from the Soviet alternative, this metal came increasingly into demand. PR gained a kind of establishment support. This source of its success has been regretted by historians as often as the magazine’s outsized authority has been saluted. To critics, it was as if the recalcitrant stuff of critical thought had been weaponized. The establishment link marks the somewhat uncomfortable side of Richard Hofstadter’s famous statement in 1963’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life that Partisan Review, against much philistinism elsewhere, had become a "house organ of the American intellectual community." But had the house organ become a consensus mouthpiece?

All of this has been well chewed over by those who gnaw on the period. Some mourn

PR’s radicalism, while others mourn its supposed liberal Americanism and patriotism. Often what is said is that the

Partisan Review’s writers and commentators had a courage and freedom that we do not. And yet—oddly enough—these latter eulogies focus specifically on freedom from the university. Hail, brave ghosts who address a "public" of "educated general readers" on a sunlit plaza of the mind, undamaged by specialization and professionalism, pretension and ideology! ("Not to be overly dramatic, but I sometimes think,"

reflected Russell Jacoby on more recent times, "we face the rise of a new intellectual class using a new scholasticism accessible only to the mandarins, who have turned their back on public life and letters.")

Personally, I do not think that any of these old conditions or attunements preclude, by their absence in our own time, a new birth of public intellect just as great as that of the earlier period. Nor do I think "the university" is to blame for the change that does exist. If I try to say what really does seem meaningfully different in our moment, I’m led elsewhere. Something has gone wrong in our collective idea of the "public."

When The Chronicle Review invited me, with the spur of Partisan Review’s digital reappearance, to compare it with the "state of polemic" now, in 2015, I confess my heart sank. Fools rush in where angels fear to tread, and it is so hard to distinguish in your own time what is temporary rubble and what is bedrock once you get the historical jackhammer whirring. Yet I do feel certain that quite common, well-intentioned arguments about "public writing" and polemic now are misguided, and the university-baiting is annoying. And this is not unrelated to the ways elegists are wrong about Partisan Review.

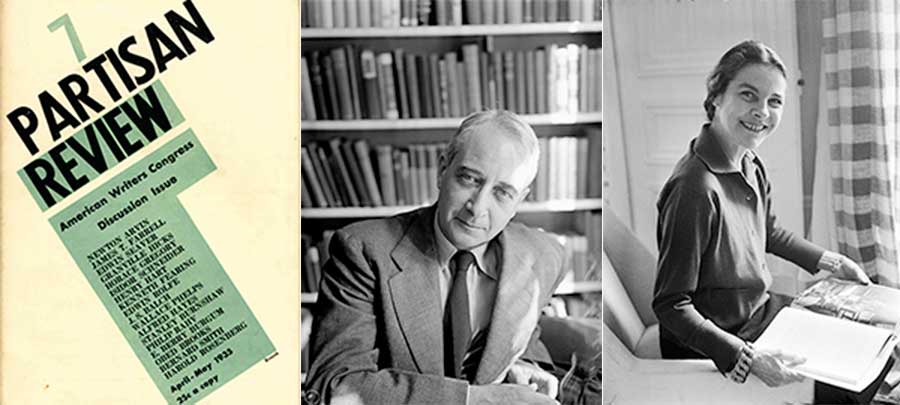

Sylvia Salmi, Bettmann, Corbis

Lionel Trilling and Mary McCarthy

So: Here are some of those things that nostalgists get wrong aboutPartisan Review, at least in its major phase from the 1930s through the 1950s. First is that it deradicalized or became merely a political vehicle of the Establishment. It’s true that it ceased to be Trotskyist, and it supported the U.S. war against the Nazis, but it still retained a vision of future socialism that would make The New York Times’s hair stand on end. The point, I think, is that one need not always water down stringent politics to be taken seriously by power; better to be superior and truthful on all fronts and let compromisers come to you.

Second is that it wholly "Americanized," coming to think of its aspirations as nationalistically American, and the United States as the true source of authority and world thought. On the contrary, Europe remained the other world—the greater world—which the New York Intellectuals continued to view as the Olympus they must try to live up to and steal fire from. Our much newer solipsism, in which American thought, predominating globally, has no other geographical place to look up to and emulate, seems quite new (and perilous)—not at all the situation in evidence in 1945 or 1960.

Third, though most complicated, is the idea that Partisan Review and its thinkers and theorists made their lives outside of the university. This might have been true among wealthy belles-lettrists and little magazine modernists of 1920; it was not true by 1950. A more democratic layer of intellect meant fewer thinkers with "independent means"—which meant that nearly everybody eventually had to teach. Irving Howe became a professor at Brandeis, Daniel Bell at Harvard; Lionel Trilling was already at Columbia, with F.W. Dupee, and both Sidney Hook and William Barrett were at NYU. Hannah Arendt spent her career at the New School, Saul Bellow much of his at the University of Chicago, Leslie Fiedler at the University of Montana, while even poor Delmore Schwartz taught creative writing everywhere he could. Even PR’s editors, Philip Rahv and William Phillips, moved into teaching. The magazine itself wound up supported in later years by Rutgers and then Boston University.

Dieto Uchitel

The editors of n+1 in 2005. Mark Greif, second from left, says he mistakenly thought "the languishing professoriate's reservoir of erudite rage seemed a natural resource waiting to be unlocked."

At the arrival of the Great Recession, in 2007-8, I ruefully reminded friends and students that the Depression of the 20th century, despite its miseries, had been surprisingly good for intellect. I think we have all the dislocation, injustice, and economic inequality we need, when we look at our America—and the classes of writers, teachers, arguers, dreamers, "petty bourgeois" or proletarian, have indeed even been flattened and equalized a bit, in their salaries and prospects. Maybe they need to be flattened even more, to truly take the measure of popular life in America. But the outrages on offer are surely outrageous enough. As for depoliticization: Students stew in philosophies of radical social change on one side, and observations of the corruption in the present order on the other. I don’t know anyone’s bookshelf without its Marx and Wollstonecraft, its Chomsky and Naomi Klein. The thing we’ve lost is really party politics, and it has been replaced by music-centered subculture as the main beacon for the organizing (and self-organizing) of youth. Scratch through the surface of any little magazine of the last 30 years and you’ll find the inspiration of ’zines and DIY punk rock (hip hop may serve a parallel function through different channels). But that may be a subject for another occasion.

Which leaves the question of the university. The economics of higher education in the contemporary moment may be bad for many of us—teachers, students, and temporary passers-through. But, again—this should not be a priori bad for public intellect or public debate. Quite the opposite. A large pool of disgruntled free-thinking people who are not actually starving, gathered in many local physical centers, whose vocation leads them to amass an enormous quantity of knowledge and skill in disputation, and who possess 24-hour access to research libraries, might be the most publicly argumentative the world has known.

And yet the philosophical and moral effect of "universitization" remains, I think, the most poorly explained phenomenon of intellect from the late decades of the 20th century up till now. I don’t mean that we don’t know the demographic shifts or historical causes, ever since the GI Bill. We have enough statistics. I mean that we don’t have convincing speculative histories or insightful accountings of the qualitative effects on ideas.

Confusingly, the "universitization of intellect" names overlapping changes. The most important yet underappreciated was the process by which nearly all future writers of every social class came to pass through college toward the bachelor’s degree. Another was the progress by which more writers, including journalists, reviewers, poets, and novelists, as well as critics and historians and social scientists, drew parts of their livelihood from periodic university teaching, whether they were tenured professors or not. (This had clearly begun already by the "golden age" of public intellect, in the 1940s to 1960s, as I’ve suggested.) The third, a corollary, was the vocational integration in which formerly independent literary arts (fiction, poetry, even cultural criticism) came to be taught as for-credit courses and degree-granting programs—with a credentialing spiral whereby newly minted critics and intellectuals needed to have taken those courses and degrees in order to pay rent by teaching them.

Our task is to make "the public" more brilliant, more skeptical, more disobedient, and more dangerous.

Nevertheless, the seriousness, intensity, and nobility of the university did not therefore get communicated back outward, through writers’ remaining ties to the commercial sphere. The university remained an accident, a blemish on the face of literature. The distaste for academia, judging it essentially compromising to writers’ and critics’ practice, remains a compulsory conceit for maintaining or resuming a place in commercial work. One must simultaneously differentiate oneself from the university spiritually and embed oneself within it financially. I’d venture that the long-term trend of the university, for culture, has thus been to be much more encompassing and yet seem to matter less to that ultimate phantasm, "the real world." "Matter," that is, visibly—to identity, in authority of open expertise in the arts and humanities, or pride of tone or university style—whenever university skills (and salary) facilitate extra-university utterance. (This does not answer what sorts of unconscious influences and determinations of art and ideas may be happening underneath.) But this was never a foregone conclusion.

Here’s a personal confession. At the start of n+1, our conception anticipated, in fact depended upon, striking a chord among under- appreciated academics. We founders were in our late 20s. We had graduate degrees (fistfuls of M.F.A.’s, M.A.’s, and even one M.Phil. among us), but not jobs. Looking upward to those who had gone further, the languishing professoriate’s reservoir of erudite rage seemed a natural resource waiting to be unlocked. I, for one, was certain that if we recreated a classic public-intellectual mode, by sticking difficult argument in the public eye—keeping it elevated, superior, but unfattened by "literature reviews" and obeisances to mentors—junior professors would flock to our banner and create classic public-intellectual provocations like those of yore. Just think of the ranks of assistant professors, even newly tenured associates, all frustrated, all possessed of backlogs of fierce critical arguments (with bankers’ boxes of research), throwing caution to the wind and freeing these doves and falcons from their cages. Fly free, beautiful birds!

The huge personal disappointment—and it puzzled me for a long time—was that junior professors did not, by and large, give us work I wanted to print. I knew their professional work was good. These were brilliant thinkers and writers. Yet the problems I encountered, I hasten to say, were absolutely not those of academic stereotype—not esotericism, specialization, jargon, the "inability" to address a nonacademic audience. The embarrassing truth was rather the opposite. When these brilliant people contemplated writing for the "public," it seemed they merrily left difficulty at home, leapt into colloquial language with both feet, added unnatural (and frankly unfunny) jokes, talked about TV, took on a tone chummy and unctuous. They dumbed down, in short—even with the most innocent intentions. The public, even the "general reader," seemed to mean someone less adept, ingenious, and critical than themselves. Writing for the public awakened the slang of mass media. The public signified fun, frothy, friendly. And it is certainly true that even in many supposedly "intellectual" but debased outlets of the mass culture, talking down to readers in a colorless fashion-magazine argot is such second nature that any alternative seems out of place.

This was emphatically not what the old "public intellect," and Partisan Review, had addressed to the public. Please don’t blame the junior professors, though. (Graduate students, it must said, did much better forn+1, as they do still.)

Suppose we try a different, sideways description of the old public intellectual idea. "Public intellect" in the mid-20th century names an institutionally duplicitous culture. It drew up accounts of the sorts of philosophical, aesthetic, and even political ideas that were discussed in universities more than elsewhere. It delivered them to readerships and subscriberships largely of teachers and affiliates of universities—in quarterly journals funded by subscriptions, charitable foundations, and university subsidies. But the culture it made scrubbed away all marks of university affiliation or residence, in the brilliant shared conceit of a purely extra-academic space of difficulty and challenge. It conjectured a province that had supposedly been called into being by the desires, and demands, of "the real world." And this conceit, or illusion, was needed and ultimately embraced on all sides—by the writers, by the readers, by the subsidizers—even, in fact, by parts of that "real world" itself, meaning bits of commerce, derivative media, politics, and even "official" institutions of government and civil society. The collective conceit called that space, in some way, into being.

But the additional philosophical element that made this complicated arrangement work, and the profound belief that sustained the fiction, on all sides, and made it "real" (for we are speaking of the realm of ideas, where shared belief often just is reality), was an aspirational estimation of "the public." Aspiration in this sense isn’t altogether virtuous or noble. Nor is it grasping and commercial, as we use "aspirational" now, mostly about the branding of luxury goods. It’s something like a neutral idea or expectation that you could, or should, be better than you are—and that naturally you want to be better than you are, and will spend some effort to become capable of growing—and that every worthy person does. My sense of the true writing of the "public intellectuals" of the Partisan Review era is that it was always addressed just slightly over the head of an imagined public—at a height where they must reach up to grasp it. But the writing seemed, also, always just slightly above the Partisan Reviewwriters themselves. They, the intellectuals, had stretched themselves to attention, gone up on tiptoe, balancing, to become worthy of the more thoughtful, more electric tenor of intellect they wanted to join. They, too, were of "the public," but a public that wanted to be better, and higher. They distinguished themselves from it momentarily, by pursuing difficulty, in a challenge to the public and themselves—thus becoming equals who could earn the right to address this public.

Aspiration also undoubtedly included a coercive, improving, alarmed dimension in the postwar period. The public must be made better or it would be worse, ran the thought. The aspiration of civic elites was also always to instruct the populace, to make them citizens and not "masses." Both fascism and Sovietism had been effects of the masses run wild (so it was said). The GI Bill, and the expansion of access to higher education after 1945, funded by the state, depended on an idea of the public as necessary to the state and nation, but also dangerous and unstable in its unimproved condition. This citizenry would fight for the nation. It would compete, technically and economically, with the nation’s global rivals. And it must hold some "democratic" vision and ideology to preserve stability. Even the worst elitists could agree to that. Hence the midcentury consensus that higher education should "make," or shape, "citizens" for a "free society"—which one hears from the best voices, and the worst, from that time.

Those of us attached to universities can feel, as strongly as anyone, how ideologies of the "public" have changed drastically from the older conception. After all, it’s on the basis of this increasingly servile, contemptuous, and antinational vision of "the public" that universities are being politically degraded, in vocational rationales for the humanities and the state’s lost interest in public higher education. The national indifference, from the top down, to the mass, the many, the citizenry, the public, from the 1970s to the present, expresses a late discovery that the old value and fearsomeness of the public had been erroneous. The mass public was no longer threatening, or needed. After Vietnam, the public was no longer needed for military service, as an all-volunteer army would fight for pay without inspiring protest. The public was no longer needed for mass production, as labor was exported. A small elite of global origin, but funneled through American private universities, would design all the new technological and financial instruments that could keep U.S. growth and GDP high in aggregate, though distributed unequally.

Protest, not stability, seemed to arise in the late 1960s from a mass national education that put students and professors together too comfortably in the universities, especially at the best of the public systems, as in California. Nor would the rest of the public rise up and make trouble, even as it was left behind for the sake of the new order. A scary and capable democratic public would not find a voice in TV, or Hollywood, or the forms of communication that flattered the public as if we liked to be dumb and powerless, nowhere coercing it with intellectual aspiration. All the American public, the many, were needed for was as continuing consumers—as long as that demand did not place too much burden on the state for support—and this could be accomplished in the short term by loose credit. And even as wages stagnated, goods appeared, in the form of new, underpriced fruits of globalized labor, their miraculously low costs to be put onto Visa and MasterCard. I am only recounting a history that we have all learned to experience as cliché.

If all that’s so, there’s little enough that intellectuals in any location can undo immediately with a flourish of rhetoric or a stroke of a pen. But insofar as a debate about priorities—and ideals—will continue anyway in our little corner of the world, we ought to try to set it the right way round. The idea of the public intellectual in the 21st century should be less about the intellectuals and how, or where, they ought to come from vocationally, than about restoring the highest estimation of the public. Public intellect is most valuable if you don’t accept the construction of the public handed to us by current media. Intellectuals: You—we—are the public. It’s us now, us when we were children, before the orgy of learning, or us when we will be retired; you can choose the exemplary moment you like. But the public must not be anyone less smart and striving than you are, right now. It’s probably best that the imagined public even resemble the person you would like to be rather than who you are. (And it would be wise for intellectuals to stop being so ashamed of ties to universities, however tight or loose; it’s cowardly, and often irrelevant.)

If there is a task, it might be to participate in making "the public" more brilliant, more skeptical, more disobedient, more capable of self-defense, and more dangerous again—dangerous to elites, and dangerous to stability; when it comes to education, dangerous to the idea that universities should be for the rich, rather than the public, and hostile to the creeping sense that American universities should be for the global rich rather than the local or nationally bounded polity. It is not up to the public intellectual alone to remake "the public" as a citizenry of equals, superior and dominant—that will take efforts from all sides. But it is perhaps up to the intellectual, if anyone, to face off against the pseudo-public culture of insipid media and dumbed-down "big ideas," and call that world what it is: stupid.

Mark Greif is an assistant professor of literary studies at the New School and a founder and editor of the journal n+1. He is the author of The Age of the Crisis of Man: Thought and Fiction in America, 1933-1973, just out from Princeton University Press.