Vyrt, a real-time streaming video platform that combines merchandise sales, fan management and social engagement, and he's an active investor in startups includingNest, Blue Bottle Coffee, and mobile-payments platform Stripe

http://www.fastcompany.com/3035975/generation-flux/find-your-mission

GENERATION FLUX'S SECRET WEAPON

In a world of rapid change and great uncertainty, the greatest competitive advantage of all may be at your very core.

Chipotle CEO Steve Ells doesn't mince words. "Our investors are here for only one reason: great returns. They want to make money." Chipotle's customers, Ells says, are equally focused: "They care about taste, value, and convenience." What about the company's ballyhooed mission of "Food With Integrity"? Ells laughs acerbically: "Is that ever going to be the reason people come into the store? 'Oh, I want to eat food with integrity right now!' I don't think so."

Yet mission is exactly what makes Chipotle so much more than just the taste of its barbacoa. "Food With Integrity" animates every decision the company makes, from the slaughterhouse to the food line at your local outlet to the strategic planning at the Denver headquarters. When Ells, who's a chef himself, launched Chipotle 21 years ago, he focused on fresh ingredients. That evolved over time into an awareness of all the different forms of exploitation inherent in traditional fast food--of animals, of the environment, and even of customers. Chipotle has distinguished itself from the Burger Kings and McDonald's of this world by relying on "naturally raised" meat that is antibiotic- and hormone-free, by dropping trans fats from its cooking before doing so was in vogue, and by offering organically certified beans and avocados. "It's the responsible thing to do," says Ells. Other chains reheat frozen items in a mechanized system. At Chipotle, Ells points out, "we're actually cooking. If you walk into the refrigerator, you'll see fresh onions and peppers and raw meat that isn't tenderized or treated in any way."

That mission drives Chipotle's sales and marketing tactics. Chipotle eschews dollar menus and other standard fast food gimmicks, offering a narrow range of meal options at relatively high prices. When Chipotle's ad agencies couldn't find a way to make "food with integrity" a compelling sales proposition, Ells dumped them and brought marketing in-house. Now the company is winning industry awards, and building valuable customer loyalty, through campaigns such as The Scarecrow. The online video and game about farmers and fresh food has become a best seller on the App Store, downloaded nearly 700,000 times. This distinctive approach has fueled Chipotle's growth. The company now has some 1,700 stores, up from 1,350 two years ago; revenue is $3.6 billion, up more than $1 billion over the same time; and Chipotle's market cap doubled to a whopping $21 billion.

When I ask Ells about another large company's mission statement--one that revolves around being the "best" in its industry--he cuts me off: "What kind of a mission is that?" he asks. "I don't want to shit all over his mission. It's his mission. He can have whatever he wants, but that kind of thing wouldn't work for us." At another point, I ask about his competition. If traditional fast-food chains change their practices in reaction to Chipotle's success, would he see that as a good thing overall, because it broadens the food-with-integrity culture? Or would he view it as a threat? "It's a joke," he replies. "You know those guys, right? They can't change. The culture is just too ingrained. Which bodes very well for Chipotle."

Steve Ells and Chipotle are hardly alone in embracing what Ells calls a "loftier" vision for the enterprise. "If you want me to make decisions that have a clear ROI," another renegade CEO declared at a public shareholder meeting earlier this year, "then you should get out of the stock, just to be plain and simple." A few months earlier, that same renegade had announced that his company was committed to "advancing humanity." He claimed that his frame for decision making was moral: "We do things because they're just and right." This emphasis on social goals over financial performance seems almost revolutionary--and yet the renegade is none other thanTim Cook of Apple, CEO of the most valuable company in the world.

Ells and Cook represent a rising breed of business leaders who are animated not just by money but by the pursuit of a larger societal purpose. Their motivation may be personal, emotional, and, yes, moral; and yet their idealism is rewarded in the marketplace. In a world that is evolving faster than ever, companies such as Apple and Chipotle--and Google and PepsiCo, and even fashion brands like Eileen Fisher--rely on mission to unlock product differentiation, talent acquisition and retention, and even investor loyalty. The more they focus on something beyond money, the more money they make.

Their success calls into question many entrenched assumptions about corporate success and the frameworks and priorities that shareholders and strategists have come to rely on. So much of the business world remains primarily obsessed with quarterly financial performance. But these short-term metrics can distract from an enterprise's long-term impact on the world, and that distraction can result in products and other offerings that undercut value creation. At a time when the pace of change is unrelenting, this may be the biggest weakness in today's economic system.

I've written several articles recently about something I call Generation Flux. This refers to the group of people best positioned to thrive in today's era of high-velocity change. Fluxers are defined not by their chronological age but by their willingness and ability to adapt. These are the people who are defining where business and culture are moving. And purpose is at the heart of their actions. Don't confuse this with social service. For these folks, a mission is the essential strategic tool that allows them to filter the modern barrage of stimuli, to motivate and engage those around them, and to find new and innovative ways to solve the world's problems. Their experiences show the critical advantages of building mission into your career and your business. Businesses that find and then live by their mission often discover that it becomes their greatest competitive advantage.

JARED LETO, 42

Actor, musician, tech investor

Embodying the blurred lines of many modern careers, Leto has morphed from the soulful Jordan Catalano in My So-Called Life into the raucous lead singer of Thirty Seconds to Mars, and also from entertainer to entrepreneur and tech investor. Leto says his decisions as an entrepreneur and an artist arise from the same creative place.

Embodying the blurred lines of many modern careers, Leto has morphed from the soulful Jordan Catalano in My So-Called Life into the raucous lead singer of Thirty Seconds to Mars, and also from entertainer to entrepreneur and tech investor. Leto says his decisions as an entrepreneur and an artist arise from the same creative place.

"I don't compartmentalize. Whatever you're doing, you should be passionate about. If you're not, then say no."

EMBRACE THE CREATIVE EDGE

Backstage in Romania, Jared Leto has a few spare minutes--not to talk about acting, which earned him an Oscar for his role in Dallas Buyers Club, or singing, which has brought him an international fan base as lead singer of his band, Thirty Seconds to Mars, despite the early bashings of critics. Leto wants to talk about Leto Inc. The enterprise starts with the band, a demanding venture: It performed in Hungary two days earlier, with several other European countries ahead, then on to the U.S., Canada, most of South America, and South Africa before the tour ends. "It could last a year," Leto says, and that wouldn't be its longest road trip ever. The group is recognized in the Guinness World Records for a marathon 309-show tour that started in 2009 and ended in 2011.

This isn't enough to satiate Leto. What he really wants to do is reengineer the business of being a performer. He uses social media to connect with some 2 million Twitter followers who buy Thirty Seconds to Mars products and attend special-access events. He has directed an award-winning documentary about his battles with a former music label. More impressively, he's got a team of coders working for him in Silicon Valley on Vyrt, a real-time streaming video platform that combines merchandise sales, fan management and social engagement, and he's an active investor in startups includingNest, Blue Bottle Coffee, and mobile-payments platform Stripe.

So is he a musician, an actor, a director, or an entrepreneur? "I'm a multi-hyphenate whatever," Leto says. "I'm a creative and an artist. I make and share things with the world that hopefully add to the quality of people's lives." His entrepreneurship "comes from the same place. I don't compartmentalize," he says. "My work is never a job. My work is my life. If you work your fucking ass off, you can get a lot done."

Not many of us will ever find ourselves shirtless before thousands of Romanians screaming our name, as Leto does later that evening. But his attitude is one that we can embrace. Leto channels his creative passion into business, and more and more evidence suggests that this is the key to creating a meaningful career.

In this age of flux, people's sense of connection with their workplace has been declining. Last year, Gallup came out with a detailed study of workers across U.S. businesses. In all industries and all age groups, engagement was pitifully low. "The vast majority of U.S. workers (70%) are not reaching their full potential," the report concluded. Yet in those pockets where passion for the job flourished, productivity, levels of customer service, and profitability were all higher than average. "Companies with engaged workforces have higher earnings per share," the report stated. Perhaps most important (and surprising) of all: "Engagement has a greater impact on performance than corporate policies and perks."

"There has always been a psychological contract between workers and corporations, often unconscious," says motivation expert Marcelo Cardoso of Brazilian health care company Grupo Fleury, who has studied employee engagement across cultures. He notes that the demise of loyalty-based contracts (job security in exchange for commitment to the organization) has resulted in a more transactional relationship between worker and company: bonuses, stock options, and other compensation bind the two together. "But as the level of complexity [in business] is increasing, these types of contracts are no longer satisfying and effective for individuals," Cardoso says.

A more effective contract, he says, meshes an individual's sense of purpose with that of the company. The Gallup report notes that millennials, gen-Xers, and baby boomers consider "mission and purpose" a valuable motivator. Other studies reinforce this idea that unlocking "psychic energy," as Cardoso describes it, is less tightly tied to financial compensation, as economists had assumed. As Daniel Pink eloquently explained in the book Drive, higher pay leads to better performance only for routine, repeatable tasks; for higher cognitive efforts and creative tasks, maximizing rewards actually hurts performance.

Jennifer Aaker at Stanford University has taken this idea even further. She challenges the very notion that a pursuit of happiness is what drives us most. Her work suggests that people's satisfaction with life is higher, and of greater duration, when meaning--rather than happiness--is their primary motivation. For other professors, such as Wharton's Adam Grant, this is the difference between a life focused on "giving" rather than "taking," a difference that they believe increases productivity as well as satisfaction.

We should, of course, stop for a moment to acknowledge that choosing a career built around meaning is not a choice available to billions of people who are desperately struggling just to make enough money to find shelter and put food on the table. That is often the only "mission" that matters. But for those who have been fortunate enough to look beyond their basic needs, the motivation to do more, create more, and, yes, give more to the world--whether that is burritos or iPhones--arises directly from the personal meaning we derive from those activities. That is the way humans operate. We are not drones whose only goal is to make more money. Keeping passion out of the workplace makes no sense at all.

FOLLOW AN INSIDE-OUT STRATEGY

"Purpose is at the essence of why firms exist," says Hirotaka Takeuchi, a management professor at Harvard Business School. "There is nothing mushy about it--it is pure strategy. Purpose is very idealistic, but at the same time very practical."

Takeuchi is not the boldest-faced name at Harvard--yet. But his research offers a compelling model for mission-based business culture. Takeuchi espouses what he calls an "inside-out approach" to business strategy. With a more traditional "outside-in approach," he says, you begin by assessing the outside environment, the state of the industry and the competitive field, in order to determine the most advantageous positioning for your company. Business schools have been stressing this approach for years, but Takeuchi believes it is too narrow.

At a company built on an inside-out strategy, he explains, "the beliefs and ideals of management become the core. Why does the firm exist?" The research Takeuchi has done with Ikujiro Nonaka at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo shows that the key differentiator between enterprises is how they envision their futures. "A very bland mission doesn't resonate," he explains. A dynamic, long-term plan requires a mission that's clear, focused, and invaluable: "Look at what Walt Disney wanted: 'to create timeless, universal family entertainment,'" Takeuchi continues. "If you have those five words, there's no doubt in the mind of employees or anyone else what you're about."

This might sound touchy-feely to business leaders trained to prefer quantifiable metrics like sales growth and operating margin. Takeuchi doesn't care. "Consultants argue that strategy comes from big data," he says, "but it really comes from the heart." You can hear the cynics groan. But what if Takeuchi is right? What if an inside-out strategy creates more creative, resilient companies than those following the old outside-in approach?

ROBERT WONG, 48

Executive Creative Director, Google Creative Lab

Wong says he is guided by what he calls the four Ps: purpose, people, products, and process, in that order. Without purpose, the others would be ungrounded.

"As the world gets more complicated, with change in more and more places, it's easy to lose the big picture. There's a huge gap between the potential of people on the planet and what's really happening."

THE POWER OF PURPOSE

While speaking to dozens of Generation Flux leaders over several months, it became clear to me that there is no single formula for how to run an inside-out enterprise, no standard org chart, no "Ten Rules" that everyone follows. In fact, it makes little sense to try to prescribe one, given the range of passions that inform these businesses and the range of stakeholders they serve. But the best leaders of these enterprises do have one thing in common; they have all carefully thought through the creation of a corporate environment that helps them, and their employees, try to live by the company's mission.

Robert Wong is Executive Creative Director of Google Creative Lab, an internal skunk-works team that helps the search giant market its products and inspire its engineers. "In high school," he says, "they gave us a test every year that was supposed to give guidance about what we should do when we grew up. Every year, 'preacher' was in the top three results for me. I'm not religious, so I always discounted it. But now, it makes sense. Working with my team and others is, in some ways, preaching. It's all about providing inspiration."

Wong's approach is anything but squishy. Wong, who reports to Google Creative Lab leader Andy Berndt, says he is guided by what he calls "the four Ps," which stand for purpose, people, products, and process. Wong's four Ps are listed in descending order of importance and are starkly more humanistic than the classic four Ps that marketing students have memorized for decades--price, product, promotion, and place. "If you choose the right purpose, certain people will be attracted," says Wong. "They will be motivated and unified. They require less management oversight. Those people will then conceive and execute products, products that fit the purpose. The process fills in the open spaces. But strong purpose ties it together. You have to excavate the purpose first."

These four Ps seem to offer the perfect framework for Creative Lab. It's the work of someone who's deeply aware of the talent Google wants to attract and the mobility those very same people now take for granted. "The manager era is gone," says Wong. "Your staff can leave. They have the option to go. That's why purpose is so important. It's the best way to keep talent."

Wong's approach is broad enough to survive changing trends. For instance, it would serve Google just fine if the job market for creatives were to become less mobile. To fashion icon Eileen Fisher, who has long talked about "business as a movement," that kind of adaptability is simply part and parcel of running a mission-based company. Fisher finds herself constantly reviewing one simple-sounding but complex question: "How does my purpose connect to our company's purpose?"

EILEEN FISHER, 64

CCO, Eileen Fisher Inc.

Fisher has always tried to align her company's mission with its practices. It's an ongoing process, one that can never be perfected.

"A core value of ours is simplicity. Yet our process has gotten more complicated and our clothiers have gotten more complicated. These are not good things. Can we still be profitable and feel good about what we do? Our sales department asks me, 'What does that mean?'"

Fisher is an unconventional leader. Meetings begin with the ringing of a bell and a moment of quiet, and seating is always in a circle, giving everyone equal authority. The company has a no-email policy on weekends. Meetings before 10 a.m. on Monday and after 3 p.m. on Friday aren't allowed. The company pursues a host of sustainability efforts and advocates for in-need women and girls around the globe through the Eileen Fisher Community Foundation.

A few years ago, Fisher decided to focus more of her time on her foundation. But she eventually concluded that she could have a greater positive impact on the world by running the company. Last year, after hearing Cardoso speak at a conference, Fisher asked the motivation adviser to conduct a series of workshops for her and her executives. During one exercise, Cardoso asked Fisher to sit on a stool and imagine that she was the embodiment of her own purpose. "I don't even recall what I said," Fisher says, "but I remember feeling like I could be more fully myself, that I could bring those values to all these decisions that I make. Am I doing what's really important?" Fisher now returns to that specific stool when she's got a difficult question to grapple with. She calls it her "purpose chair." Sitting there for a few minutes a day, she says, "helps me be clearer about myself and what matters most."

Eileen Fisher Inc. has posted record earnings the past two years. "We're successful financially," Fisher says, "but we're pretty stressed out." So she's begun asking questions about the cost and meaning of financial growth. "Should we be measuring something beyond financial results? It's disruptive a little, but we're going deeper," she says. "We want to be a great company more than we want to be a big company. If selling more means creating more stress for ourselves, should we do it?"

Fisher is committed to continually fine-tuning the culture of her business. "We have purpose programs for our leaders. We're looking at getting participation from all of our employees. We're setting up a learning lab. I really believe that business is going to have to think this way."

SHAUNA MEI, 32

CEO, Ahalife

Mei, who immigrated to the U.S. from China when she was 8 years old, didn't fit in easily at school or in the workplace. Now, as CEO of an e-tailer for the fashion industry, she finally has a job that feels like a mission.

"You can only be as committed as you are today, and you have to be honest with yourself. When I wake up now, I'm very passionate about Ahalife. Some companies are built to exit; that's not what I'm after."

DON'T FORGET THE FILTER

Shauna Mei is founder and CEO of Ahalife, a high-end luxury e-tailer and one of Fast Company's Most Innovative Companies in 2013. Born in northern China, Mei came to America as an 8-year-old, traveling alone and joining her parents in the town of Moscow, Idaho. She slept on a lawn chair set up beside her parents' bed and spoke no English; she was an object of curiosity at school in a community with limited diversity. In Moscow, even her excellence--she was a math whiz--made her stand out uncomfortably. Eventually, however, she found her way to MIT, where she got dual degrees in finance and computer science. She then headed to Goldman Sachs, where she was confronted with another new, and equally foreign, culture.

"At that time, lots of large companies were getting refinanced: rental car companies, mattress companies, older industries. I wanted these large deals, but my supervisor put me on women-connected companies. I did Tampax and then Playtex, and after that I implored him, 'Can I do an oil-and-gas deal, an auto-supply company?' The next deal I got was Neiman Marcus, a luxury retailer for women."

Mei took a hard look at her career. "Am I going to fight the battle to work on industries the boys work on?" she asked herself. "Or is there a competitive advantage to work on luxury fashion business that I actually understand and enjoy?" The questioning helped Mei recognize that her background had prepared her for a unique mission: helping luxury artisans and designers develop sustainable businesses. She left Goldman and ultimately launched Ahalife.

Finding her mission wasn't an end point. Now she had to live it. Ahalife debuted at a moment when Gilt was getting raves for using flash sales to introduce luxury items at a low price to a mass audience. It didn't take long for Mei's backers, and even her employees, to raise the question: Shouldn't Ahalife follow the Gilt model? But Mei held firm. It was certainly conceivable that Ahalife might get a short-term lift, during its vulnerable infancy, by going the discount route. But Mei knew that most of the companies on Ahalife couldn't afford to stay in business in the long run if they didn't sell their products at full price. Mei believed she needed to persuade high-end customers that her luxury products were worth paying for. In the three years since then, she has gradually added more vendors and more customers. "Now we have over 2,000 brands," Mei says, "and we're nearing break-even."

A clear mission has helped Naithan Jones, CEO of AgLocal, apply a similar filter to his business. Jones doesn't have the background you'd expect from the founder of a startup helping family farmers tap into local markets. He was born in England to a British mother and an American father who left when he was young. But he eventually married a woman from a farming family, had two kids, and, despite never attending college, landed a job at the prestigious Kauffman Foundation, which encourages entrepreneurship around the country. Listening to his in-laws talk about the challenges farmers faced competing in a digitized world, he came up with the idea for AgLocal. He quit Kauffman; he and his wife sold off everything they owned and soon moved to San Francisco. Once in the Bay Area, he persuaded VC Ben Horowitz of Andreessen Horowitz to back AgLocal.

The company worked hard to develop a compelling software platform that helps farmers sell directly to restaurants and to meat wholesalers. But earlier this year, right around the time AgLocal was included in Fast Company's Most Innovative Companies list, Jones was confronted with his toughest decision. AgLocal had not been able to sign as many customers as Jones had anticipated. "We reached an inflection point," he says. "Do we create better software for meat wholesalers and restaurants and become a software company? Or do we try to do something better for the farmers, get them better margins by going direct to consumers?" Like Mei, Jones found some investors and employees leaning toward resetting the mission. Like Mei, he resisted. "I said no," he declares. "This is why we started this business. One day maybe we'll build a software company, but not today." Last summer, Jones's vision was rewarded when AgLocal won a contract to supply meats to Amazon Fresh, the Seattle behemoth's growing local grocery business.

These kinds of decisions are what Jared Leto calls "employing the power of no." He knows that he can't take advantage of everything that comes his way. "I never wanted to make the most movies or to make the most albums," he explains. "We all want to say yes, because with yes comes so much opportunity, but the power of no brings focus and engagement. I've got a standing rule for a couple of years: no new projects. The list of creative projects I've got, I'm going to stick with them. What you're doing, you should be passionate about. If not, say no."

NAITHAN JONES, 39

CEO, AgLocal

Jones's startup connects small farmers to buyers. He could have made it a broader software platform, but he chose to stay on mission. One reason? He married into a farming family, giving him a personal sense of the challenges.

"I was brought up to not complain, be tough, and work hard. If you get rewarded, great. If you don't, keep working and keep focused. It was the core ethic."

PREPARE FOR PARADOX

Having a mission is a powerful tool. Even so, living your mission can be enormously complex. Case in point: the efforts of Indra Nooyi, CEO of PepsiCo, the $66-billion-a-year global snack and beverages giant.

Nooyi acknowledges that she straddles two eras. "Every aspect of business as we know it is being disrupted because of technology, geopolitics, the democratization of media, and so on. Some people see this as an opportunity. Others are scared to death." She talks about the pressure to "make money at all costs" and the difficulty of balancing the long-term needs of PepsiCo with the short-term expectations of its shareholders. "To run a business responsibly, you have to run it for the duration of the company," she says, "rather than the duration of the CEO."

Nooyi operates PepsiCo under a mission statement she calls "Performance with Purpose." This is not a sexy or emotional phrase; in fact, it is so banal as to seem almost without meaning. But the strategy that underlies it is not entirely dissimilar from what CEO Ells is executing at Chipotle. Nooyi's brand was built selling sugar water and salty snacks, yet she has a customer base that is increasingly health conscious. So how does she integrate those realities and still satisfy return-hungry investors?

"When we articulated this notion of performance with purpose, people said, 'Oh, this is corporate social responsibility,'" Nooyi says. "Wrong. This is not about how we spend the money we make. The focus needs to be on how we make the money." Her mission-oriented strategy has three pillars. First, she explains, "we had to transform the portfolio to include healthier products." Second, she aimed to reduce the use of plastic, fuel, and water. This was not just an environmental initiative, she says: "Our sustainability agenda helps communities, but it is also linked to financial performance." The third pillar is about people--in her case, a whopping 270,000 employees: "How do we create an environment in PepsiCo where everybody can bring their whole selves to work? That helps recruiting and retention."

Do these policies come from the heart, as Takeuchi would say, or are they calculated? The answer is: both. Many people have questioned the authenticity of Nooyi's mission; would a company with a truly significant social agenda introduce a Mountain Dew fruit-juice combo as a breakfast drink, as PepsiCo did last year in an effort to get more young people to consume its caffeinated elixirs? It's hard not to wonder how much the "performance" dictates Nooyi's "purpose." PepsiCo's stock lagged behind that of rival Coca-Cola for several years, but it has delivered nearly double the return over the past 24 months. Depending on the analyst you speak to, that's either because Nooyi's "performance with purpose" is starting to pay off--or because the company has been backing away from it. The jury is still out.

Even Chipotle's food-with-integrity ideal can come into conflict with its near-term financial goals. Here's one example: Sometimes Chipotle cannot source enough sustainably raised meat to satisfy the heavy demand for its burritos. Militant food-with-integrity advocates might argue that Chipotle should pull unavailable items from its menu. But that's not the choice Ells has made. In what Chipotle calls "blackout" situations, affected stores put up signs announcing that traditionally sourced meat has been substituted for the sustainable fare customers are accustomed to. By and large, Ells reports, customers continue to order the items they want.

Does this decision make Ells a hypocrite, a leader who sacrifices his mission to maximize financial rewards? (Ells himself has profited so handsomely from Chipotle's success--he received $25 million in compensation last year--that shareholders actually rebuffed the company's executive-pay plan at this year's annual meeting.) Ells, of course, says no. The more successful Chipotle becomes, he argues, the more resources it has to encourage farmers to adhere to its standards and increase the integrity of the food supply. Turning away customers could impede that larger goal.

Situations like Chipotle's are complicated--as is so much of business. For investors and for employees, it comes down to a question of trust: Has the enterprise demonstrated in its actions and decisions a long-term and genuine commitment to its stated mission? Is there real progress that inspires engagement? Is the connection between what makes it a great business and what makes it a compelling mission authentic?

Chipotle has such a strong record that Ells has earned the benefit of the doubt. At PepsiCo, the burden is higher. Nooyi's predecessors never intended for PepsiCo to have "performance with purpose" at its core; that's why her stated task to imbue PepsiCo with mission is monstrously challenging and far from complete.

SALLIE KRAWCHECK, 49

Chair, Ellevate Network

Krawcheck, who held top banking positions at Citigroup and Bank of America, bought the women's networking group 85 Broads and renamed it Ellevate.

"The financial industry, despite its bad reputation, can do a lot of good in the world. But it has defined itself about money and not about meaning at all. I believe it is good for American business and for the global banking system to have more diversity in leadership."

BANKING ON A NEW WALL STREET

If there is a segment of the business world that seems hostile to the idea of a purposeful mission, it is Wall Street. Big Finance has epitomized the outside-in approach and celebrated the pursuit of maximum dollars. Wall Streeters are not, of course, a breed without conscience; the Robin Hood Foundation, to cite one example, raises millions for genuinely laudatory programs. (And of course, the alleged purpose of banking is to help fund projects and companies that create value and jobs.) But in light of the economic meltdown, government bailout, and Occupy Wall Street's critique of the 1%, even positive measures can feel like whitewashing. Wall Street as a brand has become defined by helping the rich get richer.

All of this makes the tale of Sallie Krawcheck immensely compelling. Krawcheck has had "the dubious distinction," as she puts it, of having worked for seven different CEOs in the financial services industry. She first attracted notoriety at Sanford Bernstein, where she was hailed as "The Last Honest Analyst" on the cover of Fortune. Her reputation for independence was a key reason that she was tapped by banking icon Sandy Weill to take over brokerage Smith Barney in the wake of conflict-of-interest investigations by then–New York State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer. Krawcheck's star continued to rise, as she became CFO of Citi and then head of wealth management at the firm. It's an impressive sequence, the tale of a woman in what is still largely a man's world, a gadfly in clubby Wall Street, who became an influential insider.

Now, however, Krawcheck is not sure she was ever fully part of the club. During the financial crisis, in 2008, she was fired by Citi. She had lobbied Citi's board of directors to reimburse clients who had put their money into a particular set of investments that had flopped. After much discussion, the board agreed with her plan, but other powerful executives at Citi were unhappy. A few months later, she lost her job.

"If you had asked me, when it happened, if I got fired from Citi because I'm a woman, I would have told you absolutely not," says Krawcheck, who has always resisted efforts to connect her professional achievements (and setbacks) to her gender. "But now, I'd say, not exactly."

Krawcheck isn't alleging a misogynist conspiracy. She has come to believe there is a more subtle problem confronting Wall Street. "I was invited to leave," she says, "because I had a fundamentally different business perspective than the powers that be." So she's made it her mission to safeguard that different perspective. Last year, Krawcheck took over an organization of more than 30,000 professional women called85 Broads and renamed it Ellevate Network. "We survey our women every week, and we ask about their priorities in taking a job," she says. "Gentlemen put money at No. 1; women make it No. 4. Meaning and purpose are No. 1 for women."

"At Citi," she continues, "we sold alternative investments that people thought were low risk, and they weren't. We were dumb. I advocated for returning some of the clients' money. I felt like it was the right thing to do and the positive business decision, to demonstrate to clients that we would do right by them." But returning that money hurt Citi's earnings, which didn't help its already-troubled stock price. "I knew I would get fired."

Krawcheck says her focus has shifted to helping professional women "not because of hippy-dippy reasons, but because of the impact it can have on businesses." She now believes that "what could have averted the financial crisis [was] more diversity of perspective, of opinion." She doesn't sidestep her own blame. "I was sitting in those conference rooms, at those tables. I was one of them." But she thinks that more voices like hers could have made a significant difference. "All the research tells me that women are more client-focused than men, more risk-averse," she says.

"The financial industry, despite its bad reputation, can do a lot of good in the world. But it has defined itself about money and not about meaning at all," she says. "I believe it is good for American business and for the global banking system to have more diversity in leadership." With Ellevate, Krawcheck is both following these ideals and capitalizing on a business opportunity. "Women want mission and purpose in their investments. Companies run by women--and capital devoted to women--have performed well," she notes. So she's launched an investment fund that will focus on women-friendly, women-led companies and target female investors. "If you are looking only at middle-aged white guys," says Krawcheck, recalling the financial meltdown, "how'd that work out for you?"

CASEY GERALD, 27

CEO, MBAs Across America

Gerald's stirring graduation speech to his class at Harvard Business School called on the new MBAs to embrace the fact that businesspeople may have more of a chance to change the world than anyone else.

"Harvard Business School didn't change us. It reminded us of who we could be. It reminded us that we didn't have to wait until we were rich or powerful to make a difference. We could act right here, right now."

WRITE A NEW FIELD MANUAL

Many women in business may value mission over money, but gender alone will not be the key factor in determining the long-lasting impact of this trend. The young workers of today already embrace mission and meaning.

"Millennials are thinking that there's a double personal-professional bottom line," as Krawcheck puts it. "You've got to make a living, and you want to have an impact. Your work and values have got to be aligned." Millennials don't share the antiestablishment fervor of the '60s-era baby boomers. While 90% of respondents to a Change.org study said they would give up some financial reward in exchange for making a difference in the world, the notion that business can be a vehicle of change and progress seems only to have grown.

This year, the graduating class of the Harvard Business School chose Casey Gerald to be a student speaker at graduation. It was an inspired choice. Gerald's 18-minute speech has been viewed online more than 100,000 times. Sure, he invoked the usual calls to action of the standard graduation speaker, all the language about changing the world and making a difference. But what set his speech apart, aside from its vibrant rhetoric and sincere emotion, was Gerald's embrace of what he called "the new bottom line in business . . . the impact you have on your community and the world around you. No amount of profit could make up for purpose."

As a child, Gerald was abandoned first by his father, and then by his mother. Back then, his mission was simple: survival. Growing up in inner-city Dallas wasn't easy. He and his older sister lived with relatives and friends. "We were like the Boxcar Children--on our own," he says. A few years ago, gun-toting thieves broke into his apartment and threatened to kill him, fleeing only when police sirens sounded nearby.

Gerald stayed positive and eventually made his way to Yale as an undergrad. As was true for so many twentysomethings in recent years, things didn't suddenly get easy after graduation. He had a job lined up at Lehman Brothers, but the firm imploded before he arrived. He tried his hand at a not-for-profit in D.C.; worked on an unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign in Texas; and explored the New York City startup scene, "living on tuna fish and peanut butter," as he puts it. Understandably, Gerald entered HBS hell-bent on his own financial security. He promised himself that once he'd procured his MBA, he'd avoid startups and not-for-profits.

Yet now, after graduating this May, Gerald and a couple of classmates are running a startup not-for-profit called MBAs Across America. It matches MBAs with local entrepreneurs, in a quest to revitalize American enterprise. So much for Gerald's financial security, at least in the short-term.

"We are trying to write a new field manual for business across America," he says. "It can't be about hierarchy, leaders sitting in the corner office and going to the Hamptons while everyone else is pressing sheet metal. It can't be just pursuing quarterly-earnings considerations. Leaders can't just say, 'Let's do this because it optimizes efficiency.' There's got to be a larger vision of our future and ourselves."

Maybe MBAs Across America will follow the path of so many other student startups and peter out. Maybe Gerald will be recruited away by a higher-prestige, higher-paying opportunity. Harvard's MBA graduates are still predominantly focused on the outside-in world. More than a quarter take jobs in finance, and another quarter go into consulting. But those numbers are down from years past, in a trend that has been accelerating, especially in finance, for a decade. Change is afoot. Go online and take a look at Gerald's commencement speech. Then ask yourself if it seems likely that a young man like Casey Gerald will ever commit himself to an enterprise simply because of the compensation package, as previous generations of star MBAs might have. It seems more likely that he would employ the power of no. And isn't that a good thing?

http://www.homecrux.com/2014/09/24/21077/clock-side-table-by-soriano-blanco-doubles-up-as-lamp-in-bedroom.html

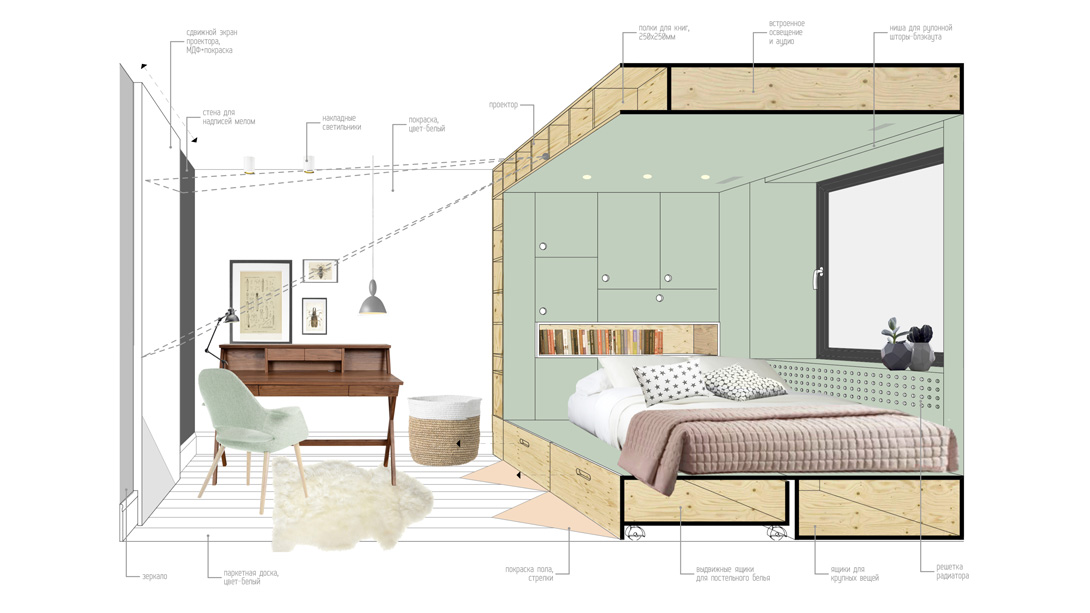

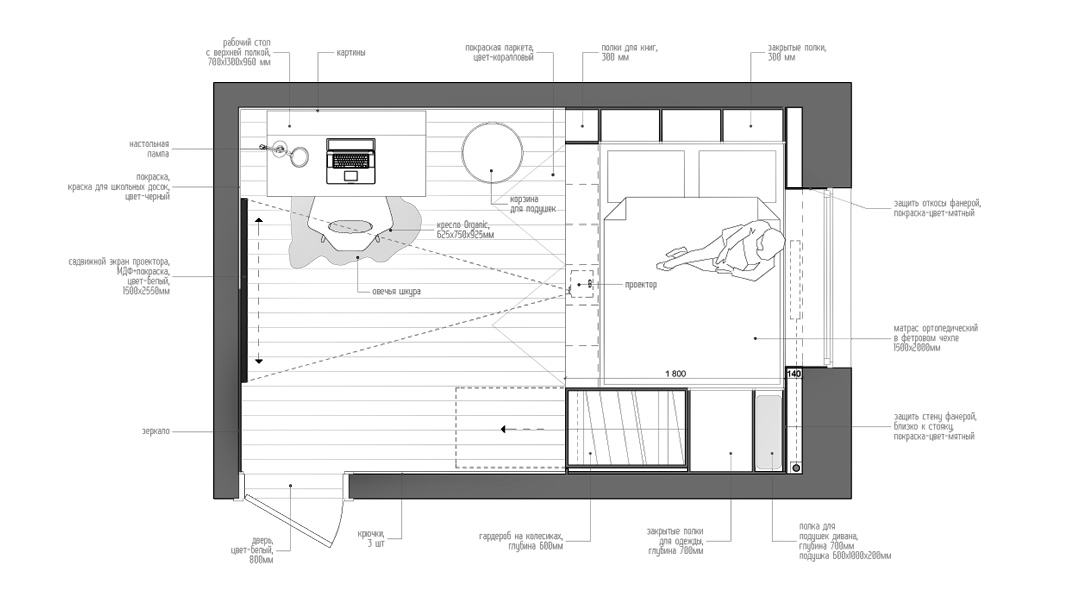

Russian architects, INT2 Architecture, has managed to create and accommodate a sleeping, lounging, studying, storage and media space all in a 14m2 room located in Moscow, Russia. Before they started working, the small room was entirely covered with many freestanding objects including a wardrobe, a working desk, single bed, book shelves and drawers for storing things. All of these things cluttered the small living space making it look crowded. So, getting the place organised, while having plenty of storage in the room was the main objective of the architects. Therefore they decided to integrate a Multipurpose Storage Box in the room, which could separate the leisure and working area and offering a lot of storage compartments to keep the things neatly organized.

The Multipurpose Storage Box is designed to function as a storage space along with a space divider. The storage spaces are integrated around a central cavity where the single bed along with sofa is placed. A wardrobe and bed linen cupboard, book shelves, drawers for holding small objects, a chest of drawers for larger things and a shelf to keep a projector are included in the storage. This large box incorporated the entire storage on one side of the room while liberating the rest of area for other things. The minimal aesthetic of the room was further enhanced by large triangular graphics on the floor and the walls of the room.

The architects have broadened the space virtually by creating the Storage Box. Moreover, they have made use of plywood as the furnishing material to keep the cost minimal. The freestanding desk, that was initially in the room is still included in the final design and instead of adding clutter to the room, it becomes an interesting furniture piece, which is enhanced by a bug art over it. The wall opposite to the Storage Box includes a full size mirror on one side and a bulletin board on the other side. A sliding panel conceals the mirror while exposing the black board and vice versa. It also functions as a projector screen area for watching movies or presentations or slideshows. The room is now fun, spacious and well organized.

No comments:

Post a Comment