Thalia (in ancient Greek Θάλεια / Tháleia or Θάλια / Thália, "the joyous, the flourishing", from θάλλειν / thállein, to flourish, to be verdant) was the muse who presided over comedy and idyllic poetry. She was the daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne, the eighth-born of the nine Muses. She was portrayed as a young woman with a joyous air, crowned with ivy, wearing boots and holding a comic mask in her hand.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Friday, October 26, 2012

Blurb from website

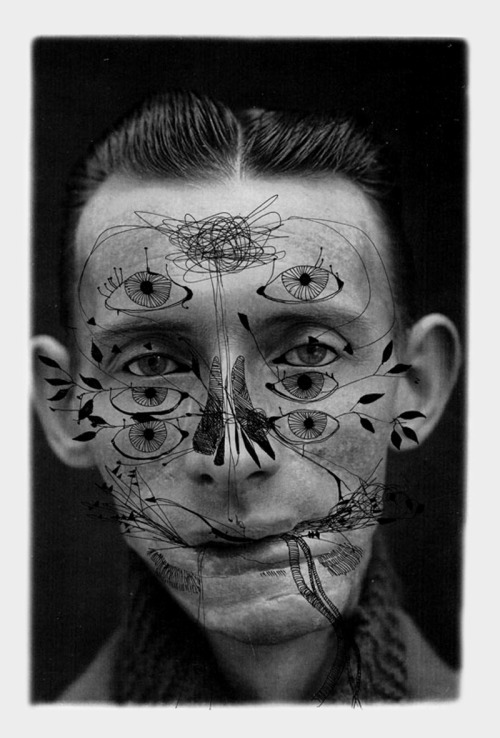

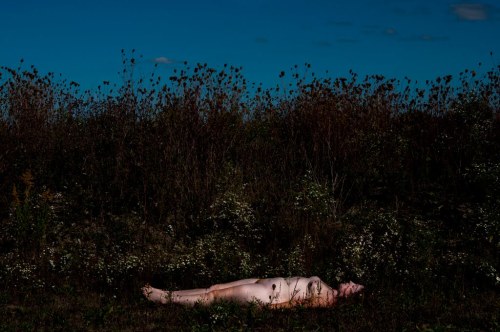

A’s work examines identity and phenomenology through storytelling. Video allows her to play with the meaning of the material as well as the subjects revealed via time based narratives. She examines the isolation and limitations of our intellect. Interested in social navigation reflecting our independence and singular modality, our perspective is both an extraordinary gift and a hauntingly isolated state. These videos glorify and regretfully illustrate our utterly unique position.

Noosphere

The Noosphere ( /ˈnoʊ.ɵsfɪər/; sometimes noösphere), according to the thought of Vladimir Vernadsky[1] and Teilhard de Chardin, denotes the "sphere of human thought".[2] The word is derived from the Greek νοῦς (nous "mind") + σφαῖρα (sphaira "sphere"), in lexical analogy to "atmosphere" and "biosphere".[3] It was introduced by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin 1922[4] in his Cosmogenesis.[5] Another possibility is the first use of the term by Édouard Le Roy, who together with Teilhard was listening to lectures of Vladimir Vernadsky at Sorbonne. In 1936 Vernadsky accepted the idea of the Noosphere in a letter to Boris Leonidovich Lichkov (though, he states that the concept derives from Le Roy).[6]

/ˈnoʊ.ɵsfɪər/; sometimes noösphere), according to the thought of Vladimir Vernadsky[1] and Teilhard de Chardin, denotes the "sphere of human thought".[2] The word is derived from the Greek νοῦς (nous "mind") + σφαῖρα (sphaira "sphere"), in lexical analogy to "atmosphere" and "biosphere".[3] It was introduced by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin 1922[4] in his Cosmogenesis.[5] Another possibility is the first use of the term by Édouard Le Roy, who together with Teilhard was listening to lectures of Vladimir Vernadsky at Sorbonne. In 1936 Vernadsky accepted the idea of the Noosphere in a letter to Boris Leonidovich Lichkov (though, he states that the concept derives from Le Roy).[6]

In the original theory of Vernadsky, the noosphere is the third in a succession of phases of development of the Earth, after the geosphere (inanimate matter) and the biosphere (biological life). Just as the emergence of life fundamentally transformed the geosphere, the emergence of human cognition fundamentally transforms the biosphere. In contrast to the conceptions of the Gaia theorists, or the promoters of cyberspace, Vernadsky's noosphere emerges at the point where humankind, through the mastery of nuclear processes, begins to create resources through the transmutation of elements. It is also currently being researched as part of the Princeton Global Consciousness Project.[7]

For Teilhard, the noosphere emerges through and is constituted by the interaction of human minds. The noosphere has grown in step with the organization of the human mass in relation to itself as it populates the Earth. As mankind organizes itself in more complex social networks, the higher the noosphere will grow in awareness. This concept is an extension of Teilhard's Law of Complexity/Consciousness, the law describing the nature of evolution in the universe. Teilhard argued the noosphere is growing towards an even greater integration and unification, culminating in the Omega Point, which he saw as the goal of history. The goal of history, then, is an apex of thought/consciousness.

One of the original aspects of the noosphere concept deals with evolution. Henri Bergson, with his L'évolution créatrice (1907), was one of the first to propose evolution is 'creative' and cannot necessarily be explained solely by Darwinian natural selection. L'évolution créatrice is upheld, according to Bergson, by a constant vital force which animates life and fundamentally connects mind and body, an idea opposing the dualism of René Descartes. In 1923, C. Lloyd Morgan took this work further, elaborating on an 'emergent evolution' which could explain increasing complexity (including the evolution of mind). Morgan found many of the most interesting changes in living things have been largely discontinuous with past evolution, and therefore did not necessarily take place through a gradual process of natural selection. Rather, evolution experiences jumps in complexity (such as the emergence of a self-reflective universe, or noosphere). Finally, the complexification of human cultures, particularly language, facilitated a quickening of evolution in which cultural evolution occurs more rapidly than biological evolution. Recent understanding of human ecosystems and of human impact on the biosphere have led to a link between the notion of sustainability with the "co-evolution" [Norgaard, 1994] and harmonization of cultural and biological evolution.

Living systems are dissipative structures that create internal order by expending energy in exchange for a local reduction in entropy. This is true at every level of biological organization and increasingly so the more abstract such order becomes within living systems. For instance, genes create an abstract information framework within which multicellular organisms may modify the topology of the epigenetic information state space in order to adapt and subsequently evolve. This may include changing the genes themselves that are involved in the abstract information framework or altering the manner in which these genes coordinate their activity. Nevertheless, as complexity and, therefore, order increases in biological systems, the amount of abstraction within that system also increases. This creates, in effect, an increase in information density. At the level of the brain, this abstraction becomes evident as the information structure known as the mind. Certain theories posit that such an ordering alters the information state of the surrounding environment such that, for ever decreasing levels of entropy, there is a net local entropy deficit or "information moment" impressed upon the surrounding environment by the extant local information structures. In this way, the mind, an abstract phenomenon seated in the physical substrate of the brain, may be capable of inducing a local entropic force that, when summed among many minds simultaneously, produces an even more amplified phenomenon known as the noosphere.

Cosmogony

Cosmogony (or cosmogeny) is any scientific theory concerning the coming into existence, or origin, of the cosmos or universe, or about how what sentient beings perceive as "reality" came to be. The word comes from the Greek κοσμογονία or κοσμογενία (from κόσμος - "cosmos", "the world") and the root of γί(γ)νομαι / γέγονα ("to be born, come about"). In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in reference to the origin of the solar system.[1][2]

The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological model of the early development of the universe.[3] The most commonly held view is that the universe was once a gravitational singularity, which expanded extremely rapidly from its hot and dense state. While this expansion is well-modeled by the Big Bang theory, the origins of the singularity remains one of the unsolved problems in physics.

One problem is that there is currently no theoretical model that explains the earliest moments of the universe's existence (during the Planck time) because of a lack of a testable theory of quantum gravity. Researchers in string theory and its extensions (for example, M theory), and of loop quantum cosmology, have nevertheless proposed solutions. Another issue facing the field of particle physics is a need for more expensive and technologically advanced particle accelerators to test proposed theories (for example, that the universe was caused by colliding membranes).

Developing a complete theoretical model has implications in both the philosophy of science and epistemology. For example, it would clarify the meaningful ways in which people can ask the question "why do we exist?".

The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological model of the early development of the universe.[3] The most commonly held view is that the universe was once a gravitational singularity, which expanded extremely rapidly from its hot and dense state. While this expansion is well-modeled by the Big Bang theory, the origins of the singularity remains one of the unsolved problems in physics.

One problem is that there is currently no theoretical model that explains the earliest moments of the universe's existence (during the Planck time) because of a lack of a testable theory of quantum gravity. Researchers in string theory and its extensions (for example, M theory), and of loop quantum cosmology, have nevertheless proposed solutions. Another issue facing the field of particle physics is a need for more expensive and technologically advanced particle accelerators to test proposed theories (for example, that the universe was caused by colliding membranes).

Developing a complete theoretical model has implications in both the philosophy of science and epistemology. For example, it would clarify the meaningful ways in which people can ask the question "why do we exist?".

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Tuesday Morning Foreign Region DVD Report: "La morte ha fatto l'uovo" ("Death Laid An Egg") (Giulio Questi, 1968)

http://mubi.com/notebook/posts/tuesday-morning-foreign-region-dvd-report-la-morte-ha-fatto-luovo-death-laid-an-egg-giulio-questi-1968

Sometimes I wonder whether I'm prone to psychic flashes, or if I just have a selectively superb memory of whose powers I'm somehow unaware. For instance. The other night, I was sitting at home, doing my latest re-reading of Marx's Eighteenth Brumaire, as one will, and listening to a relatively recently acquired disc of orchestral music by Bruno Maderna, an Italian contemporary composer who died way too young. (Born in 1920, he died in 1973. Pierre Boulez, a friend, wrote a particularly striking work in his memory.) Maderna's stuff is good; he clearly absorbed all the lessons of the serialists while taking his own route with respect to instrumentation (several of his major works highlight the flute). After finishing with my reading, I did a little more research on the fellow and discovered that he had scored several films over the course of his career. For some reason, I thought, "I bet one of them was Death Laid An Egg."

And whaddya know—Maderna had scored Death Lays An Egg. Now, I had, I admit, seen Death Lays An Egg—I own the 1968 Italian film on a 2004-issued Japanese DVD, as it happens—but I hadn't looked at in a long time. So my question was, had I retained Maderna's name from my last viewing/auditing of the film, or was their something in his music—its deep seriousness, engagement with the world, and wicked hints of the sardonic—that made me associate it with this unique film?

Well, I certainly know the answer I prefer. I like to think I hooked on to a qualitative/attitudinal affinity somehow. This Death is one of the most unusual artifacts of its culture and its time. Now I think we all know that in the late 60s and early 70s, continental European cinema in particular was replete with, or at least produced more than the average number of, genre films that embedded a Marxist critique of Western economic and/or social practices into the thrills of their particular subsets. One of the most famous is the spaghetti western A Bullet For The General, costarring committed leftist Euro icon Gian Maria Volonte (who deigned to work with Godard on his rather less thrilling "Western," Wind From The East) and then similarly-activism-minded Lou Castel (Fists In The Pocket, Fassbinder's Beware of a Holy Whore).

Spaghetti Westerns, which find a natural attraction to storylines involving capital and various forms of power, political and otherwise, are a good fit for such critiques. Giallos, with their reflexive sensationalism and automatic potential for sadistic misogyny, maybe not so much. Questi's films turn the latter quality on its head in the punchline it gives to hero Marco's seemingly compulsive murder of prostitutes, which is a sideline to the film's main story, which concerns, or so it seems, a love triangle between Marco (a more abstracted than usual Jean-Louis Trintignant), his secretary (perky Ewa Aulin, who starred in Candy around the same time; what a year for her!) and increasingly dull wife (one-time Italian cinema sex bombshell Gina Lollabrigida, still a mighty handsome woman). Marco and wife run a chicken-manufacturing concern, overseen by a shadowy corporation; and one of the aberrations it has in the works is a silent, headless and wingless chicken that produces more meat. Anticipating the "man made" chickens of Lynch's Eraserhead by alomst ten years!

Questi's film takes a particularly dim view of the...what do you call them, oh yes, the "means of production," and also portrays Italy in the least tourist-attractive light possible, as a land of highways and cheap motels. Very nearly overwhelmed by this very odd film, Italian-Sex-And-Horror movie expert Adrian Luther Smith wrote of it in his superb genre encyclopedia Blood & Black Lace: "[This] incredible film demands repeated viewings and a major article to do it justice...the influence of Godard is obvious...and there are also nods to Buñuel." Yes, there are, but it's also the kind of dirty, nasty, but strangely brilliant sui generis film that exists, for whatever reason, only in particular nooks and crannies of cinematic consciousness (another good example, to name just one, is Douglas Hickox's 1972 Sitting Target), which makes finally seeing it hit with something like the force of revelation. The 2004 Japanese Region 2 disc, from King Records, is merely an okay-looking non-anamorphic 1.85 transfer that for all its lack of distinction still packs a weird wallop. And of course the only American label interested in it was Blue Underground (whose founder William Lustig is also a big booster of Sitting Target...), but a U.S. iteration can't happen without some rights issues clearing up, I hear...

And Maderna's score? Yes, it is appropriately, ironically, dissonant. ■

Written by Glenn Kenny

Published on

Sometimes I wonder whether I'm prone to psychic flashes, or if I just have a selectively superb memory of whose powers I'm somehow unaware. For instance. The other night, I was sitting at home, doing my latest re-reading of Marx's Eighteenth Brumaire, as one will, and listening to a relatively recently acquired disc of orchestral music by Bruno Maderna, an Italian contemporary composer who died way too young. (Born in 1920, he died in 1973. Pierre Boulez, a friend, wrote a particularly striking work in his memory.) Maderna's stuff is good; he clearly absorbed all the lessons of the serialists while taking his own route with respect to instrumentation (several of his major works highlight the flute). After finishing with my reading, I did a little more research on the fellow and discovered that he had scored several films over the course of his career. For some reason, I thought, "I bet one of them was Death Laid An Egg."

And whaddya know—Maderna had scored Death Lays An Egg. Now, I had, I admit, seen Death Lays An Egg—I own the 1968 Italian film on a 2004-issued Japanese DVD, as it happens—but I hadn't looked at in a long time. So my question was, had I retained Maderna's name from my last viewing/auditing of the film, or was their something in his music—its deep seriousness, engagement with the world, and wicked hints of the sardonic—that made me associate it with this unique film?

Well, I certainly know the answer I prefer. I like to think I hooked on to a qualitative/attitudinal affinity somehow. This Death is one of the most unusual artifacts of its culture and its time. Now I think we all know that in the late 60s and early 70s, continental European cinema in particular was replete with, or at least produced more than the average number of, genre films that embedded a Marxist critique of Western economic and/or social practices into the thrills of their particular subsets. One of the most famous is the spaghetti western A Bullet For The General, costarring committed leftist Euro icon Gian Maria Volonte (who deigned to work with Godard on his rather less thrilling "Western," Wind From The East) and then similarly-activism-minded Lou Castel (Fists In The Pocket, Fassbinder's Beware of a Holy Whore).

Spaghetti Westerns, which find a natural attraction to storylines involving capital and various forms of power, political and otherwise, are a good fit for such critiques. Giallos, with their reflexive sensationalism and automatic potential for sadistic misogyny, maybe not so much. Questi's films turn the latter quality on its head in the punchline it gives to hero Marco's seemingly compulsive murder of prostitutes, which is a sideline to the film's main story, which concerns, or so it seems, a love triangle between Marco (a more abstracted than usual Jean-Louis Trintignant), his secretary (perky Ewa Aulin, who starred in Candy around the same time; what a year for her!) and increasingly dull wife (one-time Italian cinema sex bombshell Gina Lollabrigida, still a mighty handsome woman). Marco and wife run a chicken-manufacturing concern, overseen by a shadowy corporation; and one of the aberrations it has in the works is a silent, headless and wingless chicken that produces more meat. Anticipating the "man made" chickens of Lynch's Eraserhead by alomst ten years!

Questi's film takes a particularly dim view of the...what do you call them, oh yes, the "means of production," and also portrays Italy in the least tourist-attractive light possible, as a land of highways and cheap motels. Very nearly overwhelmed by this very odd film, Italian-Sex-And-Horror movie expert Adrian Luther Smith wrote of it in his superb genre encyclopedia Blood & Black Lace: "[This] incredible film demands repeated viewings and a major article to do it justice...the influence of Godard is obvious...and there are also nods to Buñuel." Yes, there are, but it's also the kind of dirty, nasty, but strangely brilliant sui generis film that exists, for whatever reason, only in particular nooks and crannies of cinematic consciousness (another good example, to name just one, is Douglas Hickox's 1972 Sitting Target), which makes finally seeing it hit with something like the force of revelation. The 2004 Japanese Region 2 disc, from King Records, is merely an okay-looking non-anamorphic 1.85 transfer that for all its lack of distinction still packs a weird wallop. And of course the only American label interested in it was Blue Underground (whose founder William Lustig is also a big booster of Sitting Target...), but a U.S. iteration can't happen without some rights issues clearing up, I hear...

And Maderna's score? Yes, it is appropriately, ironically, dissonant. ■

John Cassavetes – BBC Omnibus: The Making of Husbands (1971)

This is a super-rare look behind the scenes of Cassavetes’ first ‘big budget’ film, Husbands. It depicts several scenes which never made it into the final film, and a few that did. Also great is to watch Cassavetes working out scenes with Peter Falk and Ben Gazzara, sitting around a table smoking, brainstorming, joking, and singing – just like Archie Gus and Harry!

Picture quality isn’t tops, being this was taken from a VHS copy from a 16mm print that’s seen better days, and it has a timecode window burned in at the bottom left, but everything is visible that counts.

From the original BBC copy:

Arts documentary series. Director John Cassavetes has been shooting a new film called HUSBANDS in London and New York. This documentary shows, with film from script sessions, locations and rushes, how three American actors, John Cassavetes, Ben Gazzara and Peter Falk, worked together to get the “unscripted moments that can never be planned for”.

[how accurate that implication of improv -- which was a usual press buzzword when discussing Cassavetes work -- actually is isn't clear, but you can clearly see Cassavetes using it to work out how scenes should go, as well as making sure any improv happens within strict boundaries when the cameras roll, if at all.]

http://worldscinema.org/2012/03/john-cassavetes-bbc-omnibus-the-making-of-husbands-1971/

Picture quality isn’t tops, being this was taken from a VHS copy from a 16mm print that’s seen better days, and it has a timecode window burned in at the bottom left, but everything is visible that counts.

From the original BBC copy:

Arts documentary series. Director John Cassavetes has been shooting a new film called HUSBANDS in London and New York. This documentary shows, with film from script sessions, locations and rushes, how three American actors, John Cassavetes, Ben Gazzara and Peter Falk, worked together to get the “unscripted moments that can never be planned for”.

[how accurate that implication of improv -- which was a usual press buzzword when discussing Cassavetes work -- actually is isn't clear, but you can clearly see Cassavetes using it to work out how scenes should go, as well as making sure any improv happens within strict boundaries when the cameras roll, if at all.]

http://worldscinema.org/2012/03/john-cassavetes-bbc-omnibus-the-making-of-husbands-1971/

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

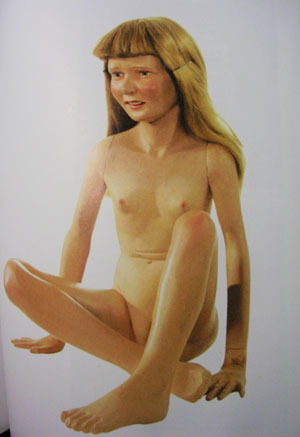

Ruth Francken

homme, chaise, 1970

Lilith, 1970

Jean-Paul Sartre, 1983

Iannis Xenakis, 1979-82

Samuel Beckett (detail), 1984-85

Televenus, 1969

Four and Seven, 1969

Conflits du monde, 1970

Jose Celestino Mutis

Beginning in 1763, Mutis proposed to the king that he sponsor an expedition to study the flora and fauna of the region. He had to wait 20 years for the authorization, but in 1783 the king authorized his expedition (one of three royal botanical expeditions to the New World at about that time). In the interim, Mutis concentrated on commercial and and mineralogical projects, not neglecting medicine. He also studied the social and economic conditions of the viceroyalty, and continued to expand his collection of flora and fauna. On December 19, 1772 he was ordained a priest. He was in regular correspondence with scientists in Spain and elsewhere in Europe, particularly Carolus Linnaeus.

Mutis led the Royal Botanical Expedition, established in 1783, for 25 years. It explored some 8,000 km2 in a range of climates, using the Río Magdalena for access to the interior. He developed a meticulous methodology that included the harvesting of the samples in the field together with detailed descriptions, including data on the surroundings of each species and its utility. Hundreds of plants were discovered and described. More than 8,000 plates, plus maps, correspondence, notes and manuscripts were sent to Spain. His museum consisted of 24,000 dried plants, 5,000 drawings of plants by his pupils, and a collection of woods, shells, resins, minerals, and skins. These treasures arrived safely at Madrid in 105 boxes, and the plants, manuscripts, and drawings were sent to the botanical gardens, where they were relegated to a tool-house.

However much of the work was wasted because the results remained unedited and unanalyzed. Also, the collation between the notes and the plates was lost during the transfer to Spain. His work on the species and varieties of Chinchona had lasting influence.

He determined the longitude of Bogotá by the observation of an eclipse of a satellite of Jupiter and was a major influence on the construction of the National Astronomical Observatory.

In March 1762, at the inauguration of the chair of mathematics at the Colegio del Rosario, he expounded the principles of the Copernican system and of the experimental method of science, leading to a confrontation with the church. In 1774 he had to defend the teaching of the principles of Copernicus, as well as natural philosophy and modern, Newtonian physics and mathematics, before the Inquisition.

In 1784, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Alexander von Humboldt visited Mutis in 1801, during his expedition to America. Humboldt stayed with Mutis for two months, and greatly admired his botanical collection.

Mutis died in Bogotá on September 11, 1808 at 76 years of age, a victim of apoplexy. Because much of his botanical work was lost or unpublished, he is known to history not as a great scientist, but as a great promoter of science and knowledge.

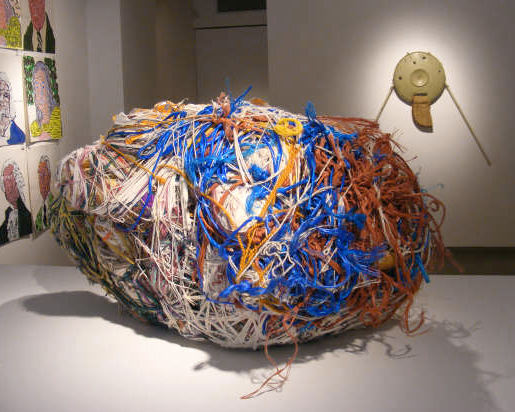

Judith Scott Yarn Sculptures

And I thought about the meaning of "asylum," and how it has been altered by institutional abuse so that it conveys opposite meanings - both a place to be avoided at all costs and a place of protection. Rescue and reunion are part of Judith Scott's story, but so is her indomitable spirit, which has found release in layered bundles expressive of a mystery we'll never fully comprehend.

"Metamorphosis: The Fiber Art of Judith Scott" will be at the Collection de l'Art brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, from October 11, 2001, to February 3, 2002.

http://www.fiberarts.com/article_archive/profiles/judithscott.asp

The urge to make associations with her work is almost unavoidable. Just for starters, they are bundled, wrapped, enfolded, sheltered, clothed, enveloped, and bandaged. They are also tough: raw, knotted, controlled. They are made slowly with accretions of "found" materials wrapped in place, much as a spider encases a fly in her web.

These found materials, to put it bluntly, are mostly stolen, or "appropriated," to use proper art-speak. But art-speak is inappropriate for discussing Scott's work. We can't begin to know what is going on inside her, for not only is she profoundly deaf, she doesn't speak, and she is also developmentally disabled, having been born with Down's syndrome almost 60 years ago.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)